What It Takes To Make a Bilingual Podcast

By Adriana Heldiz, communications committee chair

Podcast production requires many of the skills journalists are familiar with such as clear writing, compelling interviews and above all great storytelling.

It also requires producers to understand who their audience is and what they need to connect with the story.

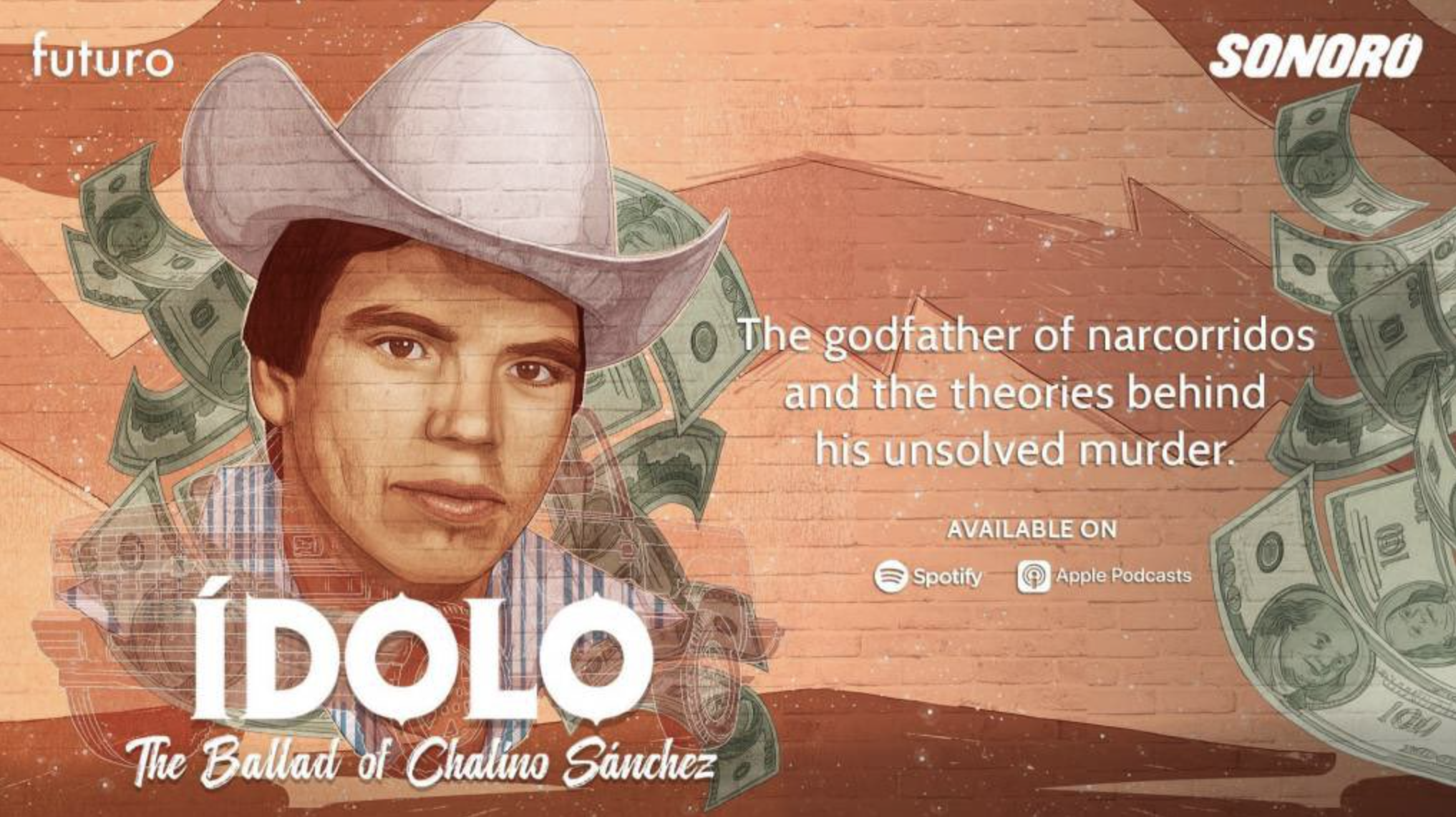

That was the challenge Erick Galindo, Sonoro and Futuro Studios faced when making Ídolo: The Ballad of Chalino Sánchez, a podcast about the godfather of narcocorridos that discusses his impact and breaks down the theories surrounding his mysterious death.

Chalino was born and raised in Sinaloa, Mexico and came to the U.S. when he was a teenager. He took on several jobs before eventually finding success as a musician.

A lot of his music focuses on the narco lifestyle in Mexico, but Chalino also captures the spirit and determination of Mexican immigrants living in the U.S.

So how do you tell the story of a man who meant so much to two similar but different audiences?

Answer: Make two versions of the same podcast and structure them to fit the needs of each audience. Galindo hosts the English version and Alejandro Mendoza hosts the one in Spanish.

NAHJ San Diego-Tijuana recently spoke to Galindo about the benefits and challenges of producing a bilingual podcast. Here’s an excerpt of that conversation.

NAHJ SD-TJ: What inspired you to make the podcast?

Galindo: I’ve been trying to tell Chalino stories for about ten years. I wanted to tell his story because I thought it was an incredible story about L.A. in the 90s and about immigrant communities.

NAHJ SD-TJ: Why did it take so long to make?

Galindo: People were concerned that there wasn’t an audience. Oftentimes, stories from marginalized communities, it’s harder for someone to take a risk on you. Anytime stories are produced, at one point or another, there’s a financial risk.

And a lot of the companies that have the money to invest in these kinds of stories have never done these kinds of stories and because they haven’t done it, they’re afraid to do it.

It’s important to have places like Futoro and Sonoro, which are actually founded and run by mostly people of color. A lot of people said no, but they said yes. They got it.

NAHJ SD-TJ: Once you got the okay to make the podcast, how long did it take to produce it?

I was working on it on my own for a long time before anybody said yes. I was doing the reporting on it on and off again for about five years. And then from there, it was just about a year of development, about six months of final reporting and another six months of writing and post-production. So with my partners ( Futuro Studios and Sonoro Media) it was two years and five years of my own, so about seven years.

NAHJ SD-TJ: What were some of the challenges you faced when making the podcast?

Galindo: It was hard to get people on the record. They were still kind of afraid to tell his story. That was the biggest one, really trying to track down this man, who he was and separating fact from fiction. There’s a lot of legends about him that exist and not a lot of facts. That was its own challenge, investigating it.

We were able to uncover more about Chalino than I think anyone has ever before and create the most in-depth investigation into his death, but mostly it was an investigation into his life and who he was.

NAHJ SD-TJ: Why did you decide to structure the podcast based on theories of his death?

Galindo: In the years that I kind of did this on my own, I realized that Chalino was basically a man made out of legend, myths and theories. Everyone I would talk to had a theory about his death and a lot of them were very similar but some of them were very crazy and off the wall. I just thought it would be fun and when I presented it to the team, I was just like, “I think we can essentially hide a cultural story in a very popular medium, which is true crime.”

The way to do that was to really be intentional. Every episode is going to talk about a theory, but it’s also going to talk about how the theory is a mixture of fact, fiction and also just the culture of immigrant experience here in the U.S. and what it was like to grow up in el rancho.

NAHJ SD-TJ: Why was it important to make this a bilingual podcast that goes beyond just translation?

Galindo: I firmly believe that the lens really matters. When you’re telling a story for an audience that’s on both sides of the border, you’re going to need both perspectives.

Originally we [Galindo and Mendoza] thought we’d trade off. “I’ll do one, you do one and we’ll get both perspectives in there.” But it didn’t work the same. It felt like we needed to tell the story through his [Mendoza] perspective and not like a directly translated version of the English one.

NAHJ SD-TJ: Making two of the same podcast must have been hard. Can you tell us more about that process? How did you coordinate with Alex, who hosted the Spanish version?

Galindo: It was very time consuming and very painstaking, but we had a good system. We had editors in both Mexico and the U.S.

We had such a strong team that Alex and I felt really supported. They were very instrumental in making sure we had a machine that was working and that made sure we put out an incredible show.

NAHJ SD-TJ: Do you think the whole process of making a bilingual podcast was worth it?

Galindo: It was definitely worth it just to see the reaction. I got so many messages from people who really felt seen. There were times [when making the podcast] were I was breaking down and wanting to quit … it was a lot of commitment, but it was definitely worth it.

It helps to prove that our stories are valuable and important, but also very commercially viable and hopefully it encourages more people to take a risk.

NAHJ SD-TJ: What advice would you give to someone who is thinking about making a bilingual podcast?

Galindo: I would say be very intentional. Don’t just go in and say, “I want to do this in Spanish because I want to reach a Spanish audience.” A Spanish-dominating audience is much more than just a language choice, it’s really a cultural choice. Just realize what you’re going into, you are doing two shows and it’s a lot of commitment.

It’s definitely worth it and adds a lot of value and more companies should definitely do it.

###